by Kelly Reeves

I was about 14 years old, anchored above a large brush pile in about 16 feet of water on the upper end of Toledo Bend Reservoir with my Great Uncle Dave Olive.

Dave lived on the lake and fished most days. Crappie catching was our mission on this day. The weather was cool this early fall morning and not a cloud in the sky. The lake was calm and slick as glass, and the only sound we heard was the occasional plop of a turtle slipping into the water, or another boat motoring by. We’d been fishing for a couple of hours without so much as a nibble, and my mood was sour enough that Uncle Dave decided to take pity on me.

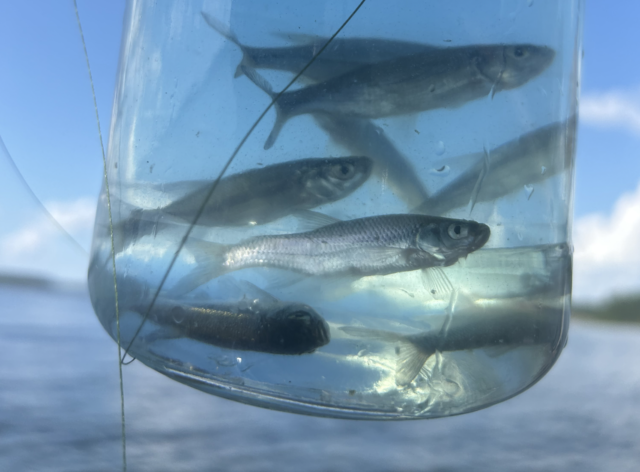

“You know what the problem is?” he asked, tilting his old cap back on his head. “These crappie got no reason to bite today. They’re just sittin’ down there fat and happy.” Before I could ask what a person was supposed to do about fat and happy fish, Uncle Dave winked at me and said, “ I’m going to let you in on my secret weapon, but you cannot share it with anyone.” He had a serious look on his face, the kind that said some secrets weren’t meant for just anyone. Then he opened his old metal tackle box—one of those dented green ones that smelled faintly of melted worms and pimento cheese—and pulled out a clear quart Mason jar with a rusty lid. The jar was filled with clean water. He put about two dozen frisky minnows in the jar and spun the lid on. The silver sides of the minnows were flashing in the sunlight, and being inside the jar magnified their size.

“You put this down where the fish are,” Uncle Dave said, “but you don’t open it. Just let ’em see it.”

I frowned. “So… we’re showing them food they can’t get to?”

“That’s right,” Dave chuckled. “And you watch what happens.”

I figured he was pulling my leg, because he was known to do such a thing, but I watched Dave tie a length of cord to the jar’s neck, lower it gently into the water beside the submerged brushpile, and set it so the jar hung just a couple feet above the fish. After five or ten minutes, we went back to fishing.

I lowered a shiner down beside the cord of the mason jar and it didn’t take long. Within minutes, the water around the brushpile seemed to stir. I could see shadows shifting, and the water ripple a bit as crappie began to vigorously try to get to the minnows. And then, as if someone had flipped a switch, our rods started bending.

Uncle Dave reeled in a fat twelve-inch crappie, then I followed with another keeper. The air filled with the sound of squeaky reels and splashing fish.

“They can’t stand it,” Dave explained between casts. “Makes ’em mad. They see those minnows, hear ’em, smell ’em even, but they can’t get to ’em. So they turn on whatever else is in the area. Which, lucky for us, is what’s on our hooks.” We caught a limit of crappie that day, and as a thank-you, Dave dumped the minnows from the jar into the lake before we left.

From that day on, I kept a jar in my own tackle box.

Years later, I learned that a lot of the old men around the lake swore by the trick. It wasn’t quite as secret as Uncle Dave let on. Some used Mason jars. Others used big pickle jars, mayonnaise jars, even the occasional glass peanut butter jar with the label still stuck on the side. The uppety fellows used store-bought, clear bait buckets with screw-on lids. But the principle was always the same: put live minnows where the crappie can see them, but can’t eat them, and you turn passive fish into competitive, aggressive ones.

The science of it—if there is such a thing—is simple. Crappie are schooling fish. They’re used to competing for food, especially when it’s scarce. Show them food that’s right there but untouchable, and it stirs up frustration. That frustration makes them strike at the next best thing, which is usually whatever’s hanging from your line.

The beauty of the trick is that it works best when nothing else does. On those hot summer afternoons when the lake feels more like a bathtub, or in late fall or early spring when a cold front blows through and locks their jaws tight, the jar can wake them up. The fish you couldn’t tempt with a perfect jig presentation or a dozen color changes will suddenly start biting.

I’ve seen it work in shallow water and deep water. Last year, fishing over a submerged cedar tree in twenty feet, we dropped a jar halfway down and watched on the sonar as crappie began moving up toward it, tightening into a swarm. By the time they reached the jar, they were fired up enough to hit anything we dropped nearby.

Of course, it’s not foolproof. Sometimes the fish just stare at it like they’re watching an aquarium exhibit, and you still have to go home empty-handed. But when it does work, you feel like you’ve outsmarted them in the simplest, sneakiest way possible.

Over the years, the story of “the jar trick” became a kind of running joke among our family and friends. Every time the bite slowed, some old boy would lean back in his chair and say, “Guess it’s time to break out the glass jar,” and half the guys would nod like it was gospel while the other half rolled their eyes.

I can still see Uncle Dave, sitting cross-legged in his old fish-n-ski boat, tying that cord to the neck of a jar, lowering it slow, and grinning when the first fish took the bait. He’d never brag or make a fuss. He just knew something the fish didn’t—and that was enough.

Nowadays, I keep my own jar tucked in the boat, just like he did. Sometimes I go months without using it. But when the lake’s too still, the fish are too stubborn, and my patience is wearing thin, I’ll pull it out, fill it with lake water, drop a few lively minnows inside, and send it down to the brushpile.

And every time I do, I swear I can hear Uncle Dave’s voice behind me, soft and amused: “Just gotta make ’em jealous, boy.”