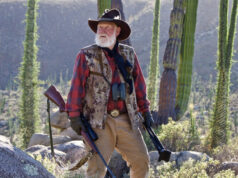

by Jim Hayes

In the late 1980s, I was hunting mule deer in the desert country of southwest Texas along the border of Mexico on a private owned low-fence ranch. I sat high atop a ridge overlooking a vast area of desert that was dotted with cactus, mesquites, and waist-high sage grass. There was no such thing as a cell phone in those days, and I had stayed out later than expected straining my eyes in search of a worthy mule deer buck.

I was sitting quietly backed up against a desert willow when I heard a whisper, “You get lost, amigo?” It was Diego, a ranch hand who worked for the ranch owner. “No. Not lost. I’m just trying to find a mule deer.” “ Mr. John sent me to find you. He worry because you should be back at camp by now,” said Diego. I said, “How did you sneak up on me without me hearing you?” I asked him. “It was easy. I learned from an Apache when I was young.” He then slowly pointed across the vast field and said, “There is a nice buck.” I looked and looked and never saw the deer he spoke of. Diego offered me the use of his binoculars to which I passed on. After he insisted several times, I took the beat up old pair of binoculars from him. They actually looked like he found them in a junk pile somewhere. I took the bino’s and lifted them to my face and the entire world lit up. Diego’s binoculars were a well used pair of Zeiss 12×50 binoculars and the quality absolutely amazed me. In short order I was able to find the buck. He had been there the entire time but I never saw him. I just thought I had a quality pair of bino’s. I was wrong. I just thought I knew how to use them. I was wrong. I thought I knew more about big game hunting. I was wrong. Diego said to me, “ Gringos look too fast. You must slow down. Slow your search. Slow your eyes. Slow your breathing. Slow down. You are looking for a deer. I am looking for an ear of the deer, or one tine of the horns, or a little piece of white hair. I find that first, then I find the rest of him.”

All I can say is thank goodness I stayed out late, Diego came to find me, and he put me through an advanced course in deer spotting. Diego, I soon learned, was an excellent outdoorsman. He had to be because wild game fed his family of six. After a few days of hunting with Diego, I began seeing many more game animals because I learned how to see them.

While hunting, the moments of silence and stillness often outweigh the bursts of excitement and action. For many hunters, the thrill isn’t solely in the stalk or the shot—it’s in the long hours spent behind glass, scouring ridgelines, timber pockets, and alpine basins in search of that telltale flicker of movement or the glint of an antler in the sun. This methodical, patient technique is known as glassing, and it remains one of the most essential and rewarding skills a big game hunter can master.

At its core, glassing involves using binoculars and spotting scopes to locate game animals from a distance. But it is much more than just peering through optics—it’s a discipline, a mindset, and often the deciding factor between a successful harvest and going home empty-handed. Whether you’re after mule deer in the high deserts, elk in the backcountry, or sheep in the alpine cliffs, your ability to glass effectively can make all the difference.

Glassing is a study in patience and detail. It’s not about scanning a mountainside in seconds or hoping for an animal to walk into view. It’s about systematically dissecting terrain, grid by grid, hour after hour. Some of the best hunters in the world may spend entire days behind glass before they even make a move. They understand that the wilderness doesn’t yield its secrets easily, and that many of the biggest, oldest animals didn’t get that way by being careless.

To glass effectively, a hunter must become part of the landscape. This means choosing strategic vantage points, minimizing movement, and allowing the world to unfold in front of them. Sometimes, a flick of an ear, the twitch of a tail, or a slight change in color is all that separates a hidden animal from the rest of the hillside. When your eyes are trained and your optics are sharp, those minute clues can become revelations.

Choosing the Right Optics

The first and most obvious tool in the glassing arsenal is the binocular. These are your primary tool for scanning broad areas and picking up general movement. Most serious big game hunters opt for high-quality binoculars in the 10×42 or 12×50 range. These provide a good balance of magnification and field of view while remaining manageable in weight and size for long days in the field.

Spotting scopes, on the other hand, are used to confirm details. Once you’ve spotted an animal with your binoculars, the spotting scope helps determine whether it’s a shooter or not. Is it the mature buck you’re after? Is that bull elk worth the long hike and grueling pack out? With magnifications ranging from 20x to 60x, a spotting scope brings you close enough to make those critical decisions without disturbing the animal.

But not all optics are created equal. Clarity, light transmission, and durability are critical. Investing in high-end glass from manufacturers like Swarovski, Leica, Zeiss, Leupold, or Vortex can be costly, but the payoff is real. When you’re trying to spot an antler tine at 800 yards in low light, the difference between good and great optics can determine whether you even see the animal.

Once you’ve chosen your optics, the next step is choosing your glassing location. Ideally, you want a high vantage point that offers an expansive view of the terrain where animals are likely to feed, bed, and travel. This might be a rocky outcrop overlooking a river valley, the edge of a timberline bench, or a saddle between ridges.

A good glassing spot offers more than just a view. It should allow you to sit comfortably for extended periods, be somewhat sheltered from the elements, and give you a hidden perch that doesn’t skyline your position. Animals are keen-eyed and wary; if you’re silhouetted on a ridge, you’re very likely to be spotted before you even lift your binoculars.

Comfort matters. Long glassing sessions can be grueling on the back, neck, and eyes. A lightweight stool or cushion, quality tripod for your optics, and layered clothing can keep you sharp and focused. Fatigue leads to missed sightings and rushed decisions.

Glassing isn’t random. It requires a systematic, almost surgical approach. Start by scanning the entire area quickly with the naked eye to get a sense of movement or major features. Then use your binoculars to break the landscape into sections. Some hunters like to use a grid pattern—left to right, top to bottom—ensuring every piece of terrain is covered.

Others prefer to “still-hunt with their eyes,” focusing on the most likely areas where animals might bed or feed like the edges of meadows, the shadows under rock ledges, the thick coverlines between timber and open ground. As you gain experience, you’ll begin to intuitively know where animals are most likely to be and where they’re least likely to show themselves.

It’s important to go slow. Really slow. It might take twenty minutes to scan one slope properly. Your eyes must learn to pick apart shapes, colors, and movements. Often, you’re looking for something out of place. A curve that breaks the straight line of a branch, a horizontal line (like a back) in a vertical forest, or a flash of white in a sea of green.

Don’t be afraid to glass the same spot multiple times. An animal can be bedded and completely invisible, then stand up and suddenly be in plain view. Changing light conditions throughout the day can also reveal or obscure details. That slope you scanned at 7 a.m. might look very different at 10 a.m.

Different animals move at different times of day. Mule deer are most active at dawn and dusk, often bedding down for hours during the heat of the day. Elk may be on their feet a bit longer in the morning and evening, but in pressured areas they can go fully nocturnal. Mountain goats and bighorn sheep, meanwhile, may stay exposed on high cliffs for hours.

Understanding the behavior of your quarry helps you know when to glass and when to move. If you know deer tend to bed on a certain slope mid-morning, then glassing that slope from a distance between 8 and 10 a.m. could give you a chance to catch them as they settle down. Likewise, evening glassing sessions often reveal animals rising to feed, offering a window of opportunity before darkness falls.

Weather also plays a major role. Overcast skies can keep animals active longer in the morning. Rain or snow can force them into cover. Wind can push them into protected pockets, and high temperatures may confine movement to the cooler hours of twilight. Each variable alters your glassing strategy.

The true power of glassing lies in allowing you to plan your stalk with precision. Once you’ve located your animal, take your time and study the terrain between you and your target. Use your optics to chart a route—look for landmarks, natural cover, and obstacles. Pay close attention to the animal’s behavior. Is it alert or relaxed? Is it alone or part of a group? Where is it likely to go if disturbed?

A well-planned stalk can take hours. It usually involves circling downwind, crawling through brush, and waiting for the right moment to close the final distance. But the beauty of glassing is that it gives you that control. Rather than stumbling into an animal and reacting in the moment, you’re operating from a position of information and intent.

Sometimes, the right call is to do nothing at all. You might locate a buck late in the day but realize there’s no safe or silent approach. Better to back out, mark the location, and return in the morning than risk blowing the opportunity with a hasty move.

The strategies behind glassing can change dramatically based on the region and species. In the West, glassing is often the primary method of locating game. Wide open spaces, mountainous terrain, and sparse cover make visibility possible, if not always easy. In contrast, in the Eastern U.S. or heavily forested areas, glassing is often more limited. Hunters there may rely more on stand hunting or short-range still-hunting.

Desert mule deer hunters may spend their days perched under the shade of a cactus, staring through the heat waves that dance across the sand. High country elk hunters might glass distant meadows from above timberline, waiting for the first orange flicker of a bull’s coat in the morning light. Every environment demands adaptation, but the fundamentals of patience, precision, and perseverance remain constant.

There’s a certain humility that glassing instills in those who practice it. You begin to understand how vast the wilderness really is, how small you are within it, and how finely tuned an animal’s instincts can be. A hunter who learns to glass becomes a student of the land. You learn where deer bed, where water lies hidden, and where winds funnel through canyons. You begin to see the landscape not just as scenery, but as a living, breathing system with patterns and secrets.

Technology has evolved—tripods have become lighter, optics more clear and powerful, rangefinders more precise—but at its heart, glassing is a traditional craft. It rewards those who slow down, observe, and respect the rhythms of nature. It’s where the romance of hunting truly resides—not in the kill, but in the endless, hopeful search for what lies hidden just beyond sight.

In the end, glassing for big game is less about optics and more about mindset. It’s a quiet pursuit, one that requires faith and focus. And for those who embrace it, there’s no more satisfying feeling than that moment when your eye catches something—a shadow moves, an antler glints—and the stillness breaks into the first heartbeat of the hunt.Because, in the wilderness, as in life, the best things often reveal themselves to those willing to look long enough.